Farmers’ movement: Need to broaden its scope by presenting a national platform

Any social transformation requires socio-economic movements which lead to a change in consciousness and bring about a political change. Leaders of farmers’ movements need to play such a role for success. At present they are seen to be only demanding concessions for themselves and agriculture. This should be widened to demanding economy-wide change since that is where the solution to their problem lies

Farmer leader Rakesh Tikait had said some months back that the farmers were prepared to sit at the Delhi border till 2024 if their demands were not met. The stand-off between the government and the farmer leaders continues since no formal talks have been held since January. The government has to take the initiative but it is not budging since it feels that it can tire out the farmers and, therefore, does not need to concede anything to them.

The Lakhimpur Kheri incident, though embarrassing, has not made the ruling dispensation change its stance on arriving at a settlement. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) has expressed concern at the simmering discontent among farmers and wants the ruling party to diffuse the situation since the impending Uttar Pradesh (UP) elections are crucial even for the national elections in 2024. Satpal Malik, the Meghalaya Governor, has stated that the farmers’ movement will dent the ruling party’s vote in large swathes of the country and that the government needs to resolve the matter amicably. Will any of this have an impact? If not, what can the farmers do?

The government’s plan

The government’s stance is based on its understanding that the farmers’ movement is a) not spreading to other parts of the country, b) the farmers’ demand is specific to the rich farmers and traders and c) the bulk of the farmers will benefit from the provisions of the three bills.

The government is banking on the divide within the farming community in every region and across the nation. Farming is very different in Punjab than in Bihar or Kerala – such as the crops grown, the cropping pattern, availability of irrigation, distribution of land across different sizes of holdings, nature of trade and extent of government support. The government is also banking on the inability of most of the farmers to articulate their long-term interests or understand what impact the three bills will have over time. It is confident that its insistence that the bills are for the betterment of the farmers will be accepted by most of the farmers if this line is repeated ad nauseam through official channels and the media.

For long, the farmers have been facing a crisis and have been protesting or, in desperation, committing suicide. So, undoubtedly reforms are required. The issue is what kind of reform will resolve the problems of the average farmer? Just any change will not do.

The government argues that the three bills meet the needs of the average farmer. It has put the entire blame for the problems faced by the farmers on the trader who sucks the blood out of the small and medium farmers. The image of the usurious sahukar, so pithily portrayed in the popular Hindi cinema from the 1950s to 1970s, is etched in the minds of the average Indian who accepts that `free markets’ will liberate the farmers and improve their lot. Add to that the positive image of the corporate sector, which offers the middle classes good jobs.

This is a picture-perfect image of the corporates entering trade in agricultural produce to liberate the farmer from the grip of the usurious traders and sahukars.

The farmers’ viewpoint

The protesting farmers argue that the shift will be disastrous for them. The corporates with their grip over policies and command over capital would be worse than the traders. They portray the three bills as pro-corporates which over time will lead to greater inequality and loss of control over their land. They fear what most monopolists do – first offer a good price to drive out competition and then raise prices. This is what the taxi aggregators have done since 2015. The farmers believe that initially the corporates may offer a good price for the produce outside the mandis, which will ring the death knell of the official markets. Once that happens, enforcing Minimum Support Price (MSP) will be impossible, as happened in Bihar, where the Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMC) mandis were abolished in 2006.

The government’s argument that it is not eliminating MSP or the APMC is theoretical but in practice that is what will happen over time as the three bills take effect. Some reports suggest that a few mandis have stopped functioning after the passage of the Bills. No wonder, the farmers demand a legally binding MSP and an assurance that the APMC system will not end over time.

Experience is that the better-off sections lead movements but that does not mean that they do not represent others’ interests. The poor neither have the time nor the means to protest since they cannot forgo their wages. They also do not have the leisure to reflect on complicated long-term issues like the functioning of markets and globalization. Even eminent economists turn out to be wrong about markets. For instance, Alan Greenspan, the Chief of the US central bank (Federal Reserve), admitted in Senate hearings in 2008 (after the global financial collapse) that he was wrong when he said that markets were ‘self-correcting’ and government intervention was not needed to check speculation.

Comparison with rich countries

Markets fail. So, can one have faith in the efficient functioning of the markets? The well-being of at least 50 per cent of the country’s population which is dependent on farming will be impacted by the Bills. The farmers say they were not consulted on these Bills – this exposes the nature of our democracy and policymaking.

It is argued that consultations have been going on and even the UPA government was in favour of implementation of similar policies. But the consultations have been with farmers and experts who are pro-market. With the launch of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1991, most economists became votaries of the Washington Consensus, which is all about marketization. But is this right for a poor country like India.

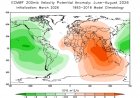

The rich countries, such as the US and the EU, recognize that agriculture markets fail and big government intervention is necessary. That is why their farmers get huge subsidies. This is feasible in these countries since a minuscule per cent of their population depends on farming – around a few per cent. In India, with 50 per cent population dependent on agriculture, the subsidy can only be small. The socio-economic conditions in India differ greatly from those in the rich countries – the scale of operation, skill levels, access to capital and marketing, etc. – so, the solution to Indian farmers’ problems has to be different.

The issue is how to sustain at a reasonable income level over 50 per cent of the population in agriculture. If the number of those dependent on agriculture is to be reduced, can the economy provide productive work to those who may get displaced? Looks unlikely. The situation for Indian farmers is worse than that of their compatriots in rich countries, where they have higher levels of both income and government support. So, Indian farmers need government support even more than that offered in rich countries. ‘Free’ markets is not the way to go.

Situation of the Indian farmers

If the government’s argument is correct that it is the rich farmers and traders from the prosperous Punjab, Haryana and Western UP who are protesting then it implies that these are the people who fear the ‘free markets’ in agricultural produce. If that is the case, can the largely impoverished small and marginal farmers, who constitute 85 per cent of all farmers, be expected to cope with `free markets’?

What is the number of farming households in the country? The PM Kisan scheme was meant to benefit 14.5 crore farms/farmer families. Of course, many of these families may have more income from non-cultivation activities like wage labour. So, it is argued that such families should not be counted as farmers and the number of farmer families comes to a maximum of 75 million. This number is key to understanding the nature of agricultural produce markets.

At 75 million, the sellers of agricultural produce have no control over the price they will get. This is unlike in most of non-agriculture where there are only a few sellers who fix their price based on their costs (called prime costs). On this cost they apply a mark-up depending on their degree of monopoly in the market so as to earn a profit. These businesses close down if there is a loss year after year.

Farmers cannot shut shop since it is a question of their survival. There is hardly any decent alternative work, so they stick around at low productivity. Those who migrate to urban areas permanently or seasonally join the unorganized sector, working at low wages, and live in illegal slums in precarious conditions.

The unremunerative price of agricultural produce implies that the surplus produced in agriculture is drained out. It fuels industrialization and urbanization. The Indian elite which decides policies, wanting to copy western modernity, went for top-down policies which marginalized agriculture and rural areas. Even when agriculturists have been in decision-making positions, they have not had a different framework. Consequently, a vicious cycle of poverty in agriculture and rural areas and growing inequality between the rural and urban areas has been perpetuated.

Farmers’ distress and indebtedness are a result of the agricultural produce not receiving a price which enables them to make a profit (as in non-agriculture). What the farmers need is favourable ‘income terms of trade’ at the farm gate. But how?

This entails an overhaul of policies and that requires a mindset change. Agriculture cannot be treated like non-agriculture, employment generation has to be buoyant, technology and investment policies have to be set right, workers have to get a living wage, taxation policies have to be modified, government intervention in the agricultural markets remains crucial, etc. Is such a radical transformation of the Indian economy feasible?

The urban and industrial elites would oppose and rule out such a transformation of the economy. The political parties would also not support such a change since they also largely work for the interest of big businesses. The alternative would be characterized as utopian – hundreds of difficulties would be listed. But what about the hundreds of difficulties being faced by Indian society in the present system – poverty, inequality, environmental degradation, etc.?

Farmers as leaders of radical change!

Any social transformation requires socio-economic movements which lead to a change in consciousness and bring about a political change. Leaders of farmers’ movements need to play such a role for success. At present they are seen to be only demanding concessions for themselves and agriculture. This should be widened to demanding economy-wide change since that is where the solution to their problem lies.

The demands should encompass various sections of agriculture and non-agriculture, workers and businesses, and they should be portrayed as for the national good. That is what business lobbies claim even when demanding concessions for themselves. They talk of what the labour, trade, taxation, investment, banking and finance, transportation, etc., policies should be.

The farmers also need to project their views on these policies from their perspective. They can also raise issues of gender, minimum wages and displacement. Since farmers, in the broader sense, are more than 50 per cent of the people, something in their interest cannot be against the national interest – the articulation has to be different. Sitting in protest at the borders of Delhi till 2024 cannot be enough; for long-term success, a new lead is required by broadening the platform to show that the ‘desirable is feasible’.

(Arun Kumar is the Malcolm Adiseshiah Chair Professor at the Institute of Social Sciences. He is the author of Indian Economy since Independence: Persisting Colonial Disruption and Indian Economy’s Greatest Crisis: Impact of the Coronavirus and the Road Ahead.)

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group