Economic and political impact of farmers’ movement

This movement has brought the Jats and the Muslims together on one platform, which is happening for the first time since the 2013 riots. Although this alliance had been formed in the bye-election for the Kairana Lok Sabha seat in 2017, it remained only a temporary one. But things are now changing.

From Bhainswal, Shamli

When I saw an unprecedented crowd gathering at a farmer panchayat in Bhainswal village of Shamli district on February 5, it made the picture emerging from the ongoing economic and political activities in the rural areas of North India pretty clear. I have always seen this village, the most prosperous in undivided Muzaffarnagar district and a leader in agriculture, as a calm one busy with itself. But the way a crowd of about 20,000 gathered at the farmer panchayat, it became apparent that an environment of economic priorities and their political fallout is in the making that would have its impact in the days to come.

About a month ago I had not seen here this kind of fervour regarding the farmers’ movement and the three central farm laws. When I went to the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU) headquarters at Sisauli in the third week of January, even then I did not see such vociferous protest and resentment on this issue. And it is not only this village. Such a situation is emerging in the entire western Uttar Pradesh (UP), Ruhelkhand and the Terai region and its impact may be visible in the UP Assembly elections to be held next year. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) may have to suffer loss in the elections. I say this not merely by seeing the attitude of people in one village but on the basis of the assessment of the farmers’ reactions during their movement, which has now entered its third month.

In fact, the farmers’ movement had started in June 2020 because of the three laws brought by the central government to bring about agricultural marketing reforms. More than seven months has passed and the movement is only gaining strength rather than weakening. Initially, the most vociferous protest was made in Punjab. Next, Haryana joined the protest in September and by November the level of protests against the laws came almost at par in both the states. Simultaneously the protest picked up in western UP as well but initially it was limited only to the token Bharat bandh in September. Even in November and December, the movement in Delhi was not getting as much support from the farmers in UP as from those in Haryana and Punjab.

By January, however, the UP farmers’ protests, too, grew vociferous. A major reason for this has been the state government not fixing the State Administered Price (SAP) of sugarcane to be paid by the sugar mills that started functioning in November 2020 for the new crushing season 2020-21 and the delay in arrear payments of cane prices last year. The state government has not announced the SAP as of February 7 and the sugar mills have started paying to the farmers at last year’s cane price of Rs 325 per quintal. But there are many sugar mills that owe dues for last season and such mills are also present in the constituency of Suresh Rana, the Sugarcane Development Minister of the state. The dues, including those for the current year, that the sugar mills owe to the farmers have reached nearly 14,000 crore rupees.

The reason why this issue is significant is that Prime Minister Narendra Modi had himself said at several election rallies that he would see to it that the farmers get their cane prices paid in 14 days. But the reality is far removed. Legally the farmers should get cane price payments within 14 days of cane supply and there is a provision of interest on the dues thereafter. But these legal provisions are not being implemented. It is worth noting that Sanjiv Baliyan, a leader of stature in the central government, is a Member of Parliament (MP) from Muzaffarnagar. Although a Minister of State, he counts among the most influential BJP leaders from western UP.

What is interesting is that, thanks to this callous attitude of the state government, once the sowing of wheat was over by mid-January western UP farmers started pouring in at the dharnas in Delhi. And when the movement seemed to be weakening in the wake of the January 26 incidents, an emotional appeal from BKU national spokesman Rakesh Tikait on January 28 changed the very face of the movement. The ongoing movement at Ghazipur on UP–Delhi border is in its strongest phase now. The reason for this is the movement consistently gaining ground in western UP.

At the same time the political character of the movement is also becoming clear now. Political parties may not be participating openly in the farmers’ movement in Haryana and Punjab, but the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) has made the movement part of its political campaign in UP. RLD has started calling a series of farmer panchayats after the BKU’s khap and farmer panchayat at Muzaffarnagar on January 29. The farmer panchayat at Bhainswal in Shamli district was RLD’s second farmer panchayat after Mathura. It was given the name of farmer panchayat but the BKU and khap leaders participated in it along with political parties. An attempt was made with the help of khaps to make Muslims too participants and this became apparent from their presence at the panchayat. The series of RLD’s farmer panchayat continues in the entire western UP, where it wields influence.

This is the circumstance that is troubling the BJP. This movement has brought the Jats and the Muslims together on one platform, which is happening for the first time since the 2013 riots. Although this alliance had been formed in the bye-election for the Kairana Lok Sabha seat in 2017, it remained only a temporary one. But things are now changing. This fact is substantiated by the presence of Ghulam Muhammed Zaula, who had been a friend of BKU’s Chaudhary Mahendra Singh Tikait, at the Bhainswal panchayat after the Muzaffarnagar and Baraut panchayats. He made the Muslims formally raise their hands at the panchayat to affirm their presence. Which means this equation is gaining ground as the anti-BJP sentiment gets unleashed. This is something even the BJP leaders accept. The ministers at the centre and other BJP officials have admitted in chats with this writer that if the farmers’ movement continues in the same fashion, it will dent their mass base and have an adverse impact on the forthcoming assembly elections.

It should be noted that BJP’s influence has rapidly increased in western UP, especially among the Jats over the last decade and a half and the party has gained from this in the decisive election results that have come in its favour since 2014. But thanks to the farmers’ movement, RLD and the Samajwadi Party (SP) are eyeing gains now and these parties are also working fast to reap dividends. Says RLD Vice-President Jayant Chaudhary in an interview with RuralVoice, “We are a political party and we are holding panchayats to strengthen the movement. We are a farmers’ party and it’s our responsibility that we strengthen the movement through a political process.”

In fact, hundred-odd assembly seats from Saharanpur to Shahjahanpur come under the region of influence of this movement. While the Jats have fully become part of the movement in most of the districts, the Sikh farmers form a strong part of this movement in the Terai districts. So, its political impact is widening. While it is the RLD that is strengthening the movement at the grassroots level in UP, this role is being played in Haryana by the khap panchayats. Large panchayats are being held there in which leaders from the BKU and other farmer organisations are invited, owing to which the movement is spreading very fast in entire Haryana even though the Delhi borders remain its hub. Also, the kind of chakka jam we witnessed on February 6 goes on to prove that the movement is firming its roots in Rajasthan as well. There can be no two opinions that the movement has united the Jats of Rajasthan, Punjab, UP and Haryana. Although other farmer castes are also becoming part of the movement, the truth is that this movement has more influence among the Jats and they also enjoy most of the leadership.

An official from the Bharatiya Kisan Sangh, the farmer organisation of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), said in an interview to RuralVoice, “We understand this loss and we are conveying what we feel to our central officials.” Similarly, the Jat MPs from the BJP are quite concerned about the issue and they have conducted several meetings regarding this so that the central leadership may be made aware of the grassroots reality of the political situation arising from the movement.

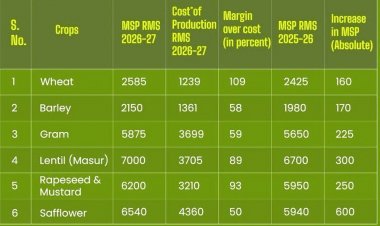

If the farmers’ movement continues for long its political and economic implications may be huge. As far as the farmers’ protests against the laws are concerned, they have now also begun to estimate the loss they are incurring on account of the implementation of the Minimum Support Price (MSP). This has also made them raise questions on the attempts made by the government to enumerate the steps it has taken in the farmers’ interests. The issues of agriculture and the farmers are coming up with various challenges for the government in the days to come which may plague the government even after the ongoing movement against the new laws.

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group