India's food security should be non-negotiable at Glasgow COP 26 meeting

In the name of biodiversity, the Indian negotiations must be extremely cautious in making any multilateral commitments that can bind us to a regulatory regime in food production and availability. The trap could be sweet with flattering quotes from some of the top leaders of the developed world as to how India should show its leadership position and become a hero of climate change. But let's not be a hero at the cost of our food security.

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP 26) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), beginning October 31 at Glasgow in the United Kingdom (UK), he would surely share with the global leaders how India has been at the forefront of protecting the environment with a greener pathway to an aspiring economy, mostly with a young population. Alok Sharma, the President of COP-26 and British Minister of State in Boris Johnson's Cabinet, would be listening with rapt attention to what India, his country of birth, has to offer to the world for a safer and better planet.

Agra-born Sharma, who would be steering some of the toughest global negotiations on making commitments to reduce carbon emissions, has a lot of empathy for India and other developing and less developed countries when it comes to taking the load of world emissions. Having been responsible for taking Mother Earth to a level of rising temperature that threatens lives and livelihood, the developed nations now would like the developing countries and the less developed nations to share the economic burden of the 'clean-up' with an equal obligation.

Alok Sharma knows it would happen and relates himself so well to the cause of the developing countries in his foreword to an official publication on the COP 26 website. “Unfortunately reducing emissions is not enough. For many nations, the picture is far bleaker. I was born in India and for a time I served as the UK government’s minister responsible for international aid – I have real sympathy with less developed countries that feel it’s for the developed industrial nations to help sort out a problem largely of their making.”

So far so good. The Indian negotiating team, comprising officials from various ministries and headed by Minister for Environment, Forests and Climate Change Bhupendra Yadav, should take India's cause where Alok Sharma leaves it. Or, to focus this article on agriculture and rural landscape, the Indian team must put things in perspective at the global level in a manner that reflects the ground reality and not fancy narratives like biodiversity. From Kashmir to Kanya Kumari, India has huge biodiversity which we need to preserve anyway. If Kerala has the right climate for growing cardamom and Punjab for wheat and mustard, the order cannot be tampered with in the name of biodiversity.

One of the things being talked about is to bring on board multilateral obligations on countries to change their pattern of food production. Even the COP-26 President talks about this: “If we are serious about holding temperature rises to 1.5 degrees and adapting to the impacts of climate change, we must change the way we look after our land and seas and how we grow our food. This is also important if we want to protect and restore the world's biodiversity.”

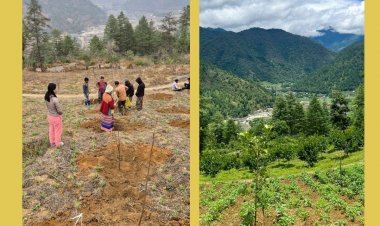

Being home to 1.30 billion people, India has been indebted to its farmers who have made us not only self-sufficient in food production but also brought about a food surplus. Thanks to abundant food availability, our government was able to provide free ration to 800 million people during the Covid -19 pandemic at a time when food scarcity became a serious challenge in several parts of the world, particularly in the less developed countries.

In the name of biodiversity, the Indian negotiations must be extremely cautious in making any multilateral commitments that can bind us to a regulatory regime in food production and availability. The good thing is that Environment Minister Yadav has kept India's negotiating strategy close to his heart and did not disclose whether we would jump at the idea of 'Net Zero Emission' by 2050, the road map for which has to be readied by 2030. The trap could be sweet with flattering quotes from some of the top leaders of the developed world as to how India should show its leadership position and become a hero of climate change. But let's not be a hero at the cost of our food security.

Our agriculture has a paradox of sorts. When the worsening climate change forces natural disasters, farmers are amongst the worst sufferers. Also, the changing weather pattern is bound to have an impact on crop yields. So, we definitely need to be a champion and agent of change, but let the obligation be first put on those who have polluted this planet. The most developed OECD countries which have exploited the natural resources in an unbridled way must live up to their promise of USD 100 billion a year towards climate change. But what we see now is financial jugglery, wherein even the commercial loans of countries are being clubbed into meeting their UNFCCC obligation.

The next 12-13 days are going to be crucial. India has to remain on top of the global climate change agenda without falling into a honey trap that puts a disproportionate obligation on our people, especially farmers, who have been brought up on the tradition and culture of worshipping mountains, rivers, forests.

(Prakash Chawla is a New Delhi-based independent journalist.)

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group