Dr Kurien: The uncanny corporate reformer

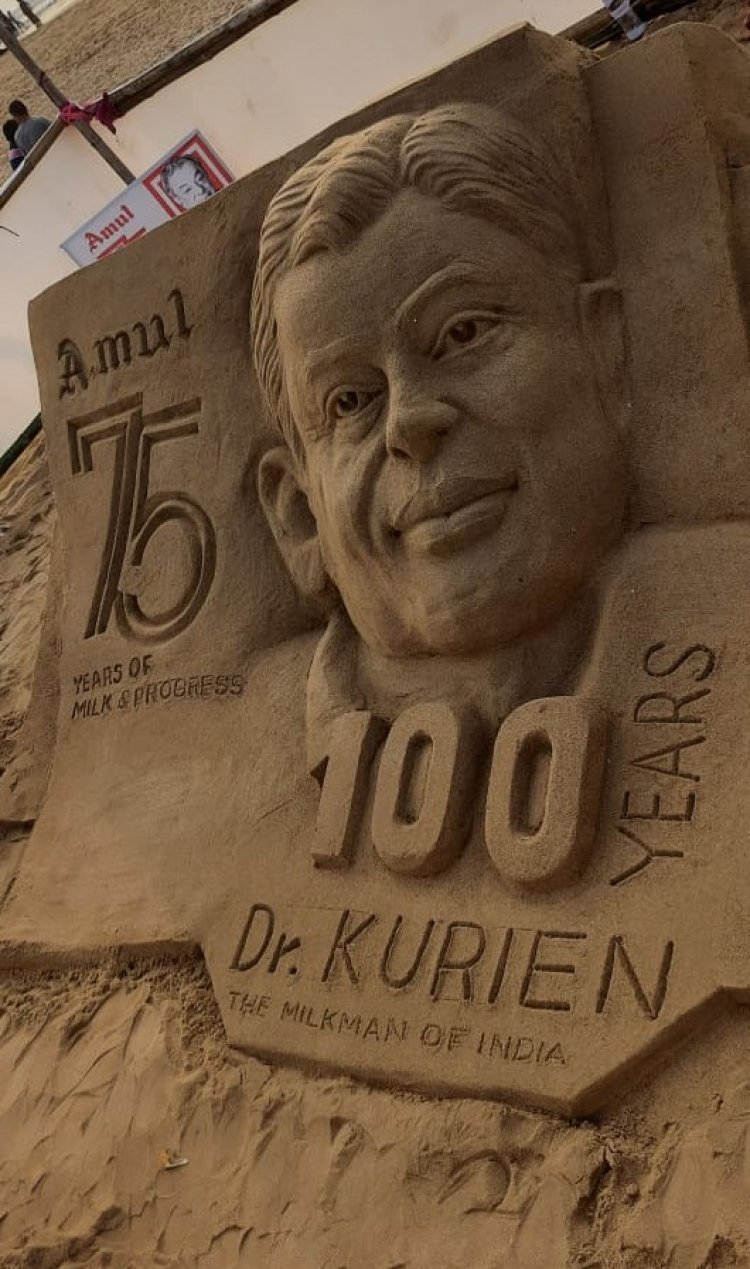

In almost every state in India, National Milk Day is being celebrated today November 26. This is a day to pay obeisance and tribute to Dr Verghese Kurien on his birth centenary. He is known the world over for his inimitable, irreplaceable and distinctive designation of “The Milkman of India”.

The Milkman of India

In almost every state in India, National Milk Day is being celebrated today November 26. This is a day to pay obeisance and tribute to Dr Verghese Kurien, born a century ago. He is known the world over for his inimitable, irreplaceable and distinctive designation of “The Milkman of India”. He made India the world’s highest milk producer and consumer and transformed it from a net importer of dairy products to a net exporter. Considering that more than eighty nations desire to adopt his universally acclaimed and unequivocally successful model of cooperative dairying, he deserves an elevated designation of “The Milkman of the World”. Rightly, the dairymen of India are campaigning for his being awarded the highest national civilian award, the Bharat Ratna.

Economic reformer

While he is remembered for dairy development, Kurien was an astute businessman and reformer. He successfully reformed the oil sector through oil cooperatives, making India self-reliant in edible oils. His project of market intervention in the oil sector was a landmark. He went for direct procurement from growers and got them remunerative prices for their fruits and vegetables. He showed the path of recreating forests through his Tree Growers’ Federation. He bound all cooperatives in a common network through the National Cooperative Dairy Federation. The federation has helped the cooperatives purchase many consumables at the cheapest prices and adopt an inter-cooperative model for the sale and exchange of dairy commodities. He would be remembered for his model agreement with states for governing and reforming the loss-making dairy federations. The model agreement incorporated that the profit made will be that of the federation and loss, if any, would be made up by the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB).

Dr Kurien has been credited for idolizing the cooperative governance model as democratic, for rural resurgence and for the empowerment of the farmer-producer at the lowest rung of the social ladder. Perhaps very few would know and realize that he had chosen the strenuous path, walked slowly and steadfastly, to reform the unruly, uncontrollable, rigid bureaucratic system that hindered social and rural development. When ‘Operation Flood” was started there was not even one state that shared, willingly or unwillingly, the blueprint of cooperative development. In fact, almost all the states had demanded that they be given their share of skimmed milk powder (SMP) and butter oil that was gifted by the World Food Programme (WFP). Each state desired that they would monetize these commodities and carry out dairy development through their own model.

This was a period when the entire animal husbandry management, milk production, processing and sale was under the departments of the state government. The progress was so dismal that the per capita milk availability was declining rather than increasing. The donated milk commodities, available in abundance, were distributed free to the consumers. This led to a serious decline in milk price, a decline in income to the milk producers and, eventually, to a decline in milk production, even as the human population went increasing.

Kurien disrupts governance model: Shift from department to corporation

To bring dairy development out of departmental control and bureaucratic governance, Kurien disrupted the governance model and convinced the states to create Dairy Development Corporations. This was the first step towards decentralization. Not willing to lose their grip on management, the state governments nominated the Directors on the Boards, most being civil servants and government officers. The Chairman as well as the Managing Director (MD) was generally from the Indian Administrative Service (IAS). The only ray of light was that at least one director was either from the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) or from the Indian Dairy Corporation (IDC) and at least one director was from the farming community.

Though much was not achieved, the governance by the Corporations became more responsive than the governance by the departments earlier. It was easier for the NDDB to make friendly inroads and get many administrative changes favouring the dairy farmers. The Corporations were found willing to adopt new technologies and techniques in animal husbandry and dairy development practices. The Corporations were open to employing trained dairy technologists, veterinarians, and management specialists for specific jobs.

NDDB spearhead teams create highways of development

This was also the time when Kurien convinced and successfully created the position of State Coordinator and positions held by middle management officer of the NDDB. He was a representative on the board and various management committees of the Corporation, the district cooperatives and steered the governance of the village cooperatives. Through him, the NDDB sent nine-member spearhead teams for the creation and spread of village dairy cooperatives. The NDDB spearhead teams were supported by the shadow spearhead teams of the corporation, whom they trained in the management and governance of dairy cooperatives. The corporations started taking over many activities that the departments of animal husbandry were implementing. Dairy cooperatives integrated milk procurement activities with providing services of breeding, nutrition and livestock health and disease control.

The first major achievement of this decentralization process was the intervention in governance by the NDDB through its spearhead teams. The corporations willingly took initiative to create dairy cooperatives at the district and the village level under the cooperative acts of the states. While village dairy cooperatives were able to elect their own management committees, the Board of Directors of the district cooperatives were still appointed by the government. This initiated the nomination of dairy farmers as directors based on political affiliation. Advantage or disadvantage, the cooperatives at the district level had increasing political pressures that were instrumental in slowly reducing the bureaucratic controls. The civil servants had to at least listen to the needs of the common dairy farmer.

The spearhead teams created highways across the state, building bridges with bureaucrats, the ministers, the politicians and above all the village-level opinion makers. The time was ripe for implementing a democratic cooperative system that was responsive to the common farmer. This was the period when suggestions for improvement in all fields by the NDDB were accepted and welcomed. The strong bureaucratic resistances were shattered.

Structural reforms in cooperatives

A decade or so of governance by corporations had brought the government closer to the NDDB. The advantages were obvious: increase in milk production and marketing. Kurien found that this was the right time to introduce another wave of reforms in governance. The NDDB created a model cooperative act and bye-laws for governance at the state, district and village levels.

Cooperative laws have been known for their restrictive provisions. These restrictive provisions have severely retarded dairy cooperatives and other cooperatives from striving to achieve their potential and function without the traditional dependency on governments.

Thanks to the pressure by the NDDB and the continued discussion at various levels in amending the existing laws and implementing standard laws drafted by the NDDB, some states have taken the initiative to liberate the cooperatives and provide them the same opportunities available to other forms of enterprise. Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Jammu and Kashmir, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka have passed parallel liberalized cooperative laws that provide an enabling and conducive environment for cooperatives and their development. Gujarat, Maharashtra and Orissa are actively considering passing new laws while Delhi and Rajasthan announced their intention to re-examine the cooperative law. The Alagh committee had recommended the incorporation of cooperatives as companies and the conversion of existing cooperatives into companies.

The Government has also been requested to define its policy and encourage the role of autonomous, self-reliant cooperatives by fully exempting them from income tax and reducing the incidence of double taxation when transactions take place between a member and its federal co-operative.

Dairy cooperative federations are born

Reforms in cooperative laws created the ground for another set of reforms. NDDB brought about another evolution by changing the dairy development corporations to cooperative dairy federations. Gradually, all the dairy corporations became cooperative dairy federations. Many of them had fully elected boards. Deficiencies still existed. There were hybrid federations, and they exist even today, with the Chairman and the Managing Director being appointed by the government, most of them being civil servants. I remember Kurien stating while delivering the keynote address to the Indian Dairy Association at the ‘Symposium on Socio-Economic Impact of The Operation Flood’ in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1983, “The Federation has amply proved that co-operatives assisted by competent professional managers can attain levels of achievement far surpassing that of many an established enterprise in the Indian corporate sector. The competence displayed by the Federation should demolish all too frequent criticism of cooperatives that their divided and shared management prevents the attainment of the highest achievements in production and marketing.” This sums up the principles of management for the dairy co-operatives. The success of the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) was its being complete in self-governance and in appointing professionals for management.

Dairy sector liberalized

Until June 1991, the dairy industry was under strict regimentation of the Industries Act. Due to this, the private entrepreneur had apprehensions about investing in this sector. Surprisingly, it was generally perceived that the dairy industry was reserved for the cooperative and not for the private enterprise. The Government of India delicensed the dairy sector in June 1991 and the private sector companies, including multinationals, were allowed to set up milk processing and manufacturing plants. The basic philosophy underlying delicensing was to encourage competition in the procurement and marketing of milk, thus increasing value for both producers and consumers. Within a year of delicensing, over 100 new dairy processing plants came into being, most of which were designed to manufacture value-added products. The establishment of new dairy plants was skewed and there was a concentration in northwest India. The creation of capacities for the manufacture of milk products was disproportionate to the availability of liquid milk. This caused a scramble for milk procurement. The shortage of marketable rural surplus of milk in comparison to the actual requirement promoted the opportunists to synthesize a look-alike of milk from vegetable oils, soap solution, urea, and other harmful ingredients and use it as milk adulterant.

The beginning of adulteration of milk on a commercial scale had Kurien seriously worried. The existence of milk production, which had been built brick by brick over a period of more than two decades, was threatened by the scourge of adulterated and contaminated milk produced and marketed by spurious milk producers. The industrial liberalization that was expected to unshackle the development and growth of this sector suddenly attacked the health and well-being of the nation.

Kurien clamps MMPO

It is to meet these strict requirements that Kurien got the Government of India (GoI) to issue the Milk and Milk Products Order (MMPO), 1992. It was in the interest of the general public to regulate the production and supply of liquid milk and milk products of desired quality. In fact, after the industrial and trade liberalization, the GoI has completely altered its role showing concern for the health of the citizen, food safety, and the quality of food products meant for local consumption and export. Like MMPO, the GOI has promulgated the Fruit Products Order to monitor the food safety and production, processing and marketing of processed fruits and fruit products and the Meat and Meat Products Order to do the same for processed meat and meat products.

Reviving sick dairy cooperatives

Reviving a sick dairy co-operative was considered, if not impossible, a very daunting task. Agreed, daunting it was. But a beginning had to be made somewhere. There are now examples of sick cooperatives that have been brought out of almost moribund condition. The dairy cooperatives in Punjab, Rajasthan, and Karnataka were taken up for revival. I was instrumental in bringing the Rajasthan Cooperative Dairy Federation (RCDF) from out of its moribund state. The process of decentralizing the staff to the district level created an irreversible impact. I remember the administration used to transfer the persons at the lowest rung to far-off district cooperatives. This caused tremendous problems and disturbed the family and life of the transferee. With the approval of the Jodhpur High Court, the entire staff up to the rank of deputy manager was permanently allocated to the chosen district cooperative. The district unions found that their survival depended exclusively on their own financial performance. Even after the NDDB exited the state, most of the district unions have been growing well financially, increasing their milk production, and diversifying their range of milk products, their sale and almost all areas of management and growth. The RCDF is now the third-largest dairy federation in India. It is a model of success of NDDB intervention with the Kurien principle that “loss if any would be borne by the NDDB”.

Wish Kurien had stayed longer!

In conclusion, I wish to quote extensively from the final evaluation report of Operation Flood. The World Bank (Wilfred and Kumar, 1998) concluded that the principles of Anand pattern for full farmer control had been facing a continuing problem of “rejection by the politicians and bureaucrats… Politicians continue to harass the cooperative system… Issues of governmental interventions, cost control and subsidies are intertwined”, leading to “mixed ownership and control” of co-operatives, which has a “subtle and corrosive effect of government intervention”. The problem has been diagnosed to the fact that the government still owns the physical infrastructure and has guaranteed the repayment of loans. The net result of this intervention is that it reduces the efficiency, increases the costs and “undermines the value of the state’s assets” and the symptom of this conflict, according to the study, is “continued appointment of civil servants as managing directors”.

The government draws the powers for interfering in the functioning of co-operatives through the State Co-operative Act, rules and regulations. There is nothing new in the information that is being furnished. Way back in 1991, the Brahm Prakash Committee had enlightened that “the essence of cooperative organization is the principle of democratic management, signifying institutional regulation by members and their elected representatives in accordance with the bye-laws. It precludes control and interference by any agency including Government…” The Committee had identified the following restrictive provisions in the State Co-operative Societies Act that empowered the Government/ Registrar to: Notify compulsory amendment of bye-laws; Nominate directors on the Management Committee/Board of Directors; Veto, annul, rescind resolutions of the Board/General Body; Give any directives; Supersede/suspend the Management Committee/Board of Directors; Restrict the terms of office of office bearers; and Compulsorily amalgamate/divide the co-operative societies. Because of these restrictive provisions, Kurien called the Registrar of Cooperatives the ‘Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh of cooperatives’.

The other problem is management intervention. The assistance is generally in the form of the appointment of a chief executive from the civil services. There is a merit to it. The experience of managing large organizations as a generalist has its advantages. It is possible to highlight many cases of success in business enterprises. The conflict arises when, compared to others, the dairy enterprise is considered backward or of secondary importance in the state. Appointments are for indeterminately brief periods. Priorities of the government in personnel placement invariably supersede the business needs of the Federation. Due to frequent changes, the organization invariably suffers from the continuous discontinuity of the chief executive. There is a consequent breach in the policy statement, implementation of policy, style of functioning, reporting and communication. In fact, the entire organizational behaviour undergoes changes so often that it suffers from severe schizophrenia. Such discontinuation in top management negates an expression of the dairy co-operative being a business organization.

Kurien, with his NDDB under him, fought relentlessly with everyone who crossed his path wrongly. His strong, sturdy, persuasive and many a time arrogant discourses made ways for creating a strong and efficient dairy sector. The sector has continued to perform, support the dairy farmer and create a resurgent rural economy. Milk production, despite much less support and investment by the government, is consistently marching ahead. India is enjoying the smooth walk on the dairy highway that Kurien structured and built. I strongly believe that it was too early for Kurien to voluntarily exit as the Chairman of the NDDB during 1998. He would have achieved much more and delivered to India many reforms and programmes leading to economic growth in the agriculture sector.

Wish Kurien had lived longer!

(Dr RS Khanna is an international dairy consultant. The views expressed here are his own.)

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group