U.S. Agriculture’s Global Influence Shrinks Amid Trade Wars and Export Declines

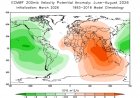

In 1980, the United States held a commanding 44% share of global wheat exports. Today, that number has plummeted to just 11%. The decline is even more dramatic in the corn market, where U.S. export share has fallen to a record-low 31%, a stark contrast to the 1970s when the country controlled over 80% of global corn trade.

Once the undisputed leader in global grain and oilseed exports, the United States is facing a steady erosion of its dominance in international agricultural markets. Over the past few decades, America’s share of global exports in key commodities like wheat, corn, and soybeans has sharply declined, with recent trade tensions threatening to accelerate this downward trend.

In 1980, the United States held a commanding 44% share of global wheat exports. Today, that number has plummeted to just 11%. The decline is even more dramatic in the corn market, where U.S. export share has fallen to a record-low 31%, a stark contrast to the 1970s when the country controlled over 80% of global corn trade.

Soybeans, once a cornerstone of American agricultural dominance, have also slipped from U.S. hands. While the U.S. commanded 80% of global soybean exports five decades ago, it now accounts for just 27%. Brazil has overtaken the U.S. as the world’s top soybean exporter, capturing much of the demand—particularly from China, the world's largest soybean importer.

The current geopolitical climate suggests the decline may not be over. Amid rising tensions with China and other key trading partners, former President Donald Trump reignited concerns in March by urging American farmers via Truth Social to prepare for a future focused on domestic markets: “Start making a lot of agricultural products to be sold inside of the United States,” he posted.

However, experts warn that such a shift is easier said than done. Currently, the U.S. exports approximately 25% of the grain it produces annually, including more than half of its soybean output. Even as domestic industrial uses of grain—such as for biofuels—have grown, exports of bulk agricultural commodities like corn, soybeans, wheat, rice, sorghum, pulses, and cotton have been on the rise. In fact, exports surged 22% last year, the largest year-on-year increase in over a decade.

While opportunities may exist to develop new domestic demand—through innovations like Sustainable Aviation Fuel or other yet-to-be-discovered industrial applications—such shifts require significant time to materialize. In the short term, the lack of reliable export markets could hurt American farmers and the broader ag economy.

One of the long-term casualties of frequent trade disputes is a country’s reputation as a dependable supplier. History has shown that once trust is broken, it can take years to rebuild. Following the grain embargoes of the 1970s and ’80s, the U.S. struggled to restore its standing. A similar pattern has emerged post-2018, after the U.S.-China trade war prompted China to favor Brazil as its main soybean source.

Moreover, America’s aggressive tariff policies under Trump have strained relationships not just with adversaries, but also with traditional allies like the European Union, Canada, and Mexico. These strained ties further complicate efforts to reassert the U.S.’s position as a leading global supplier of agricultural products.

As the latest trade war unfolds, hopes for a return to a freer, more stable trade regime remain uncertain. Until that happens, with tariffs and counter-tariffs crisscrossing borders, the global agricultural trade is caught in a race to the bottom—where the costs are high and true winners are few.

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group