India’s Farm Income Gap Puts Pressure on Budget 2026–27 Priorities

Agriculture expanded at an average annual rate of about 4 per cent between 2014–15 and 2024–25, while overall GDP grew by more than 6 per cent. Yet agriculture continues to employ about 46 pc of India’s workforce, amplifying concerns that low farm incomes are constraining consumption growth in rural India.

India’s upcoming Union Budget for 2026–27 will face mounting pressure to reorient agricultural spending as farm incomes, despite steady growth since 2014, remain too low to support rural demand or sustain broader economic momentum, according to a recent policy brief by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER).

The study estimates that the average agricultural household earned about ₹19,696 per month in 2024–25, compared with roughly ₹6,426 in 2012–13, a level broadly representative of incomes around 2014. Adjusted for inflation, real monthly farm income has risen to about ₹19,696 from roughly ₹12,173 over the past decade, pointing to meaningful but still inadequate gains.

This income trajectory has lagged overall economic growth. Agriculture expanded at an average annual rate of about 4% between 2014–15 and 2024–25, while overall GDP grew at more than 6%. Yet agriculture continues to employ about 46% of India’s workforce, amplifying concerns that low farm incomes are constraining consumption growth in rural India.

Consumption data reinforce this gap. Self-employed agricultural households spent an average of ₹3,701 per person per month in 2022–23, below the rural average and significantly lower than urban spending, underscoring weak purchasing power despite income support schemes and periodic price interventions.

Against this backdrop, the study’s findings sharpen the policy choices facing Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman as she prepares to present the Budget on Feb. 1. The report shows that income growth over the past decade has been driven less by traditional crop cultivation and more by diversification into livestock and horticulture. Livestock income rose to nearly 16% of total farm income by 2018–19 from just over 4% in the early 2000s, while the share of income from crop cultivation fell to below 40%.

Regression analysis in the study suggests that farmers with livestock earn about 86% more than those without, while those allocating larger shares of land to horticulture earn between 25% and 56% more than farmers with minimal diversification. Irrigation, education and participation in farmer-producer organisations (FPOs) also show strong positive links to income levels.

Despite this evidence, budgetary allocations remain skewed. The study notes that livestock and fisheries together account for just over 2% of central government spending on agriculture and allied activities in FY26, even as these sectors emerge as the strongest drivers of income growth. Analysts say this mismatch is likely to feature prominently in budget discussions.

The report also flags gaps in infrastructure spending relevant to high-value agriculture. Limited cold storage, processing capacity and logistics continue to expose horticulture farmers to price volatility and post-harvest losses, particularly for perishable crops such as tomatoes, onions and potatoes, which together account for about a fifth of the value of horticultural output.

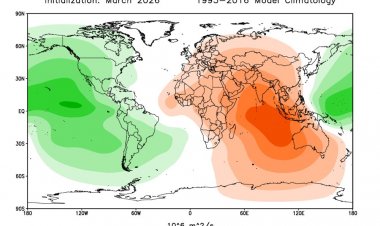

Insurance and risk management are another pressure point. Existing crop insurance schemes have limited coverage for horticulture and livestock-related risks, even as climate variability increases income uncertainty. The study suggests that without expanded coverage and faster payouts, diversification efforts could stall.

For Budget 2026–27, the findings imply a shift in emphasis rather than a simple increase in headline agricultural outlays. Greater capital allocation toward livestock, horticulture value chains, irrigation and farmer collectives may offer higher income multipliers than continued reliance on price support and input subsidies, the study indicates.

As Sitharaman prepares her eighth consecutive budget, the challenge will be whether fiscal policy can pivot from supporting farm output to structurally raising farm incomes—an issue that has become increasingly central to India’s growth narrative a decade after 2014.

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group