Reforms mean controlling input costs; food subsidy goes to run ration shops, not pocketed by farmers

There is a strong disappointment amongst those who feel that the repeal of the three farm laws is a serious setback for the much-touted agricultural reforms. It is being argued that unless the private sector gets into agriculture, Indian farming is destined to stay where it is today. However, even as the imbroglio on MSP and the farmers continues, by no means is it the end of the road for Indian agriculture.

Now that the repeal of three controversial agricultural laws is a matter of Parliamentary procedures, there is a strong disappointment amongst those who feel that this development is a serious setback for the much-touted agricultural reforms. It is being argued that unless the private sector gets into agriculture, Indian farming is destined to stay where it is today. As of today, the investment by the private sector in agriculture is almost nil: this was a concern voiced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at a recent bankers' summit.

So, the 'reformists' hold out that unless Indian agriculture is totally thrown into market forces and asked to swim or sink, things would not change. They also contend that the government cannot go on doling out subsidies to farmers and often give the example of 'food subsidy'.

As per the current year's (2021-22) Budget, food subsidy figures stand at Rs 2.43 lakh crore and the subsidy is administered by the Ministry of Food and Public Distribution. Fair enough. Let's see where it goes. Does it go to the farmers? No, this money is spent on providing almost free ration at the ration shops both in cities and in rural areas under the National Food Security Act. But we keep screaming as if the 'Food Subsidy' is pocketed by the farmers.

According to an analysis by the PRS Legislative Research, the mandate of food subsidy is as follows: ''FCI (Food Corporation of India) and state agencies procure food grains from farmers at the government-notified Minimum Support Prices (MSPs). These food grains are provided to the economically weaker sections at subsidized prices through fair price shops under the Public Distribution System (PDS). The central and state governments provide subsidized food grains to beneficiaries under the National Food Security Act, 2013 as well as certain other welfare schemes such as the Mid-Day Meal scheme.'' Those seeking to dismantle food subsidies should then know that it would mean shutting down all the ration shops! Food subsidy goes overwhelmingly to help the poor in cities and villages, not to farmers as growers.

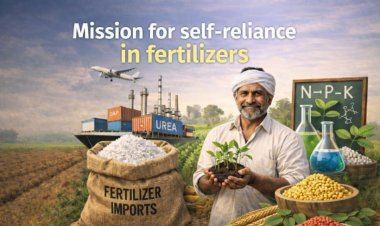

Let's return to reforms and the cherished goal of doubling the farm income and consequently the entire rural economy. The best way to do this is as follows: Considerably reduce the costs of inputs like diesel for pumping water, fertilizers, seeds, transport and warehousing. Such costs cannot be reduced without the effective intervention of the government through various tried and tested methods. Hoping for the market itself to take care of such costs would be living in a false, if not fools', paradise.

The other key tool to raise the farmers' standard is to ensure that the output price for the farm products is fair and remunerative and that the gains are not pocketed by the inefficient and the dishonest in the value chain from fields to homes. The top-heavy agriculture ministries and departments along with states have to play a proactive, rather than a reactive, role.

Let's examine the government data as given out and disaggregated in the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) of October 2021 to see how things stack up in terms of input prices for the farmers and the mandi rates for the produce.

The October WPI went up by an alarming 12.54 per cent on an annualized basis. But within the headline number lie real shockers which would have broken the back of our agriculture along with other sectors of the economy. As per this data, the year-on-year inflation for October was at 71.68 per cent for diesel, 64.72 per cent for petrol, and 14 per cent for chemicals and chemical products.

Compare this hike in important input costs for the farmers with either a decline or a modest rise in the output prices. Food articles dropped (at the wholesale mandi level — we are not talking about retail inflation) by 1.69 per cent. On the other hand, prices of cereals grew by a modest 3.22 per cent. While paddy was down by 0.55 per cent, wheat gained by 8.14 per cent. Vegetables crashed at the mandi levels by 18 per cent.

The mismatches in the prices of inputs and those of outputs in a market-driven scenario would be detrimental to the interest of agriculture, the lifeline of the majority of our people. Seeking private sector involvement, particularly from the conglomerates, and consolidation of landholdings would not solve the problem. The low productivity of Indian farming is also a function of the vagaries of weather, lack of irrigation facilities, poor transportation and logistics. The crop insurance schemes are complex and do not reach the farmers in need.

Nothing stops the private sector to seize opportunities in rural logistics and transportation, farm machinery, and tractors. After all, without bothering about the farm laws etc, Kubota of Japan is buying a majority stake in Escorts, the country's leading tractor maker, at a price of Rs 2000 per share against Rs 1600 (when the deal was sealed). Why would the Japanese invest if there were no opportunities in agriculture? The Japanese tractor and farm machinery major sees a brighter future in the Indian market. After announcing the majority acquisition plan on November 18, 2021, Kubota shared its future plans: ''By positioning EL (Escorts Ltd) as an important foundation for basic tractors in the future, Kubota will consider developing and manufacturing of basic combine harvesters and construction machinery targeting India and other emerging markets.'' Likewise, the tractor division is amongst the fast-growing business of the Mahindra group.

Yes, the imbroglio on MSP and the farmers continues, but by no means is it the end of the road for Indian agriculture.

(Prakash Chawla is a New Delhi-based independent journalist.)

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group