Process to Amrit kaal for Farmers should start with a dialogue on Food System Transformation

This article attempts to set the priorities in agriculture for Amrit kaal. ‘Amrit kaal’, to my mind, is an empowered, prosperous and inclusive India.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in a speech in 2022, envisioned a Viksit Bharat (Developed India) by 2047, where “during the coming 25 years, there will be a restructuring of all fragments of the Indian economy through rapid, profitable growth, better living conditions for all, infrastructural and technological advancements, and re-awakening the world’s trust in India. The Panch Pran or the 5 fundamentals of Amrit Kaal include the goal of developing India, elimination of any trace of the colonial mindset, honour and pride in our roots, development of unity, and a sense of duty among citizens”.

This was followed by an announcement by the Finance Minister, Ms Nirmala Seetharaman, who described the Union Budget for 2023-24, as the first budget of Amrit Kaal, and the way forward for an empowered and inclusive economy. She said, ‘The budget aims to establish a robust foundation for macroeconomic stability, with an emphasis on the empowerment of women by including a technology-driven and knowledge-based economy for New India. It provides the roadmap for promoting sustainable development through greener and futuristic (tech-driven) methods. It further aims to bring prosperity through the allocation of funds to all micro and macro-segments of the economy’.

Following these statements, a number of scholars and policy analysts delved into the ‘how to’ of Amrit Kaal. Agriculture was one of the important sectors in many of these scholarly articles. Niti Aayog (Mr. Ramesh Chand) published a detailed paper ‘from Green Revolution to Amrit kaal’. These papers contain a multitude of ideas and suggestions on the way forward.

This article attempts to set the priorities in agriculture for Amrit kaal. ‘Amrit kaal’, to my mind, is an empowered, prosperous and inclusive India. In the Prime Minister’s vision described above, ‘better living conditions for all’ is the most important pillar of this vision. We know that about 50% of the population is dependent (someway or other) on agriculture. We have seen that in times of an employment crisis like Covid times, a large portion of the workforce tend to fall back on their small piece of land to eke out a living. This brings additional pressure on the agricultural economy which is required to support a disproportionately large number of people in spite of its limited growth potential. The agenda for agriculture, inevitably, has to prioritise the needs of the large number of farmers and agricultural labour. The inclusive agenda for Amrit Kaal, therefore, has a clear priority: prosperity and welfare of the farmers and agricultural labour. This would include raising incomes of farmers, better facilities in rural areas for education, health and employment, better access to information and technology and to finance and insurance. One can make the list longer, but the focus needs to be clear!

Let me outline a few priorities:

First, indisputably, farmers need higher incomes. This cannot, as is often understood, come from productivity gains alone. Higher value creation and value capture by farmers in the value chain must be an important part of the transformation in agriculture. Designing and implementing a policy of sustainable increase in incomes of farmers requires a comprehensive shift from a consumer centric food security focus to a farmer centric one. This would involve a strategic shift in policy perspectives than a long list of ‘to do’s’ starting from productivity and technology to markets and private enterprise. No doubt, all these are important components, but the centrepiece of the strategy must be the well- being of the farmer. well-being is not just about incomes, but also access to health, education, employment and services as well.

Second, a higher degree of freedom to farmers. The farmer is hemmed in from all sides with multiple regulations on what she can or cannot do. This author has been arguing for removing multiple restrictions on farmers on various counts. These include legal restrictions and financial incentives ( a soft way to induce change in attitudes and preferences) to adopt certain practices, seeds, fertilisers, machines, finance & insurance products etc. The regulatory overburden could start from ‘date of transplanting/ sowing and end with stock limits and export bans of what are considered ‘essential’ commodities (essential from a consumer inflation perspective) covering along the way seeds, fertiliser, post-harvest, storage and marketing. A review of all these acts, rules and regulations must be a first step in increasing the degree of freedom of the farmer.

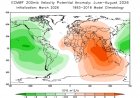

Third, enabling farmers to tackle the challenges of climate variability. Climate change issues are still to be fully understood, particularly at the local level. Understanding climate change in its local dimensions, addressing concerns of farmers’ need to grow climate appropriate crops for their livelihood security and incomes, without ignoring the larger concerns of hunger and nutrition, and bringing traditional knowledge, science and technology to play a coordinated role are important elements of this initiative.

Fourth, cleaning up the markets: the undue emphasis on consumer price inflation has to be taken out of the equation in policies related to markets. Restrictions on marketing at multiple levels of the value chain from storage to exports have worked against the farmers. More than the policies themselves, the trigger-happy manner in which these restrictions are announced is the bigger evil. There has not been any study so far on the quantum of money farmers have lost due to the decisions of the Government to control consumer price inflation. Forget a study, even the narrative that farmers are the ultimate losers in this process is not even heard n in the mainstream discussions which is always on food inflation for the consumers. Without such a narrative, the farmers have no hopes of any relief from ad-hocism.

Fifth, Research and Development to enhance farm incomes. The National Agricultural Research System has so far done a very good job of increasing productivity . This, along with private sector efforts, has resulted in quantum increases in production. While this is a great achievement, the question arises whether the farmers did increase their incomes to the extent they could have. True, increases in production and marketable surpluses do put more money in the hands of the farmer, and increase their gross income, but have they done well for themselves and their children? Most farmers would argue that their lots have become worse compared to all other professions. While R&D in the public sector will continue to dominate, it needs to refocus itself on farmer prosperity than productivity. The role of the private sector can no longer be ignored or wished away. New ways working together must be found. The phenomenal growth of startups in the Agri space is testimony to the increasing influence of private technology providers in the sector. This is likely to grow manifold in the next two decades.

Sixth, preserving natural resources. The unscientific exploitation of natural resources like soil and water has raised major concerns about the future of agriculture. Valid scientific questions have been raised about the long term sustainability of the ‘business as usual approach’ in exploiting natural resources. There are many, who advocate a complete shift to Natural Farming . Scientists do not seem to find much merit in this ‘ paramparagat Krishi only’ approach. Their doubts are not without justification. But to say only a ‘green revolution (GR)’ approach will work is also an extreme view. This GR mindset has, knowingly or unknowingly, distorted the policy in favour of unsustainable consumption of fertilisers and water leaving the farmers who conserve natural resources in the lurch without any financial support from the government. This, clearly, is not going to help the sustainability cause. The policy must change to discourage overuse and encourage conservation.

Seventh, the consumer. ‘Consumer is king!’ Naturally, we do not ask questions about the king. It is time we did. Should consumers pay a fair price to the farmer? Do they deserve to get cheap food at the cost of the farmer? (Market non-distorting subsidies with the taxpayers’ money is a different issue and not discussed here). Should uninhibited use of legal measures like export bans to benefit the consumer and cause losses to farmers continue? Should not there be a serious attempt at reducing food waste at the consumer end? Is this not a national waste of resources which deserve to be penalised? Food loss at the post harvest, transport and storage levels are not insignificant. This has to be addressed through technology, logistics and management.

Digitalisation, Artificial intelligence (AI) and Robotics: The new ‘tech’ interventions like digitalisation, AI , robotics etc have already demonstrated their potential as a disruptor in many fields. Many parts of the agricultural sector are likely to be influenced by these factors. Drones being used widely in agricultural operations is already a reality. Tech savvy entrepreneurs are filling many of the traditional gaps in agriculture and farmers are using these new products without any hesitation. A policy to synergise the capacity of our young tech entrepreneurs with the public research & extension support system has to find a prominent place in the policy.

Finally, a serious attempt at Food System Transformation. Whenever this subject is raised, the standard response is ‘this will not work’. Part of the problem is the difference in perception of what exactly is the transformation. Since the subject is discussed widely in the developed world, there are fears that countries in the West are trying to force us back to a food deficit country. Some of these fears arise from the half-baked ideas being thrown around in international seminars and workshops. It is time that we, in India, look at system inefficiencies and have our own blueprint for a food system transformation. We have the capacity to do this and we should not shy away from it. This is unarguably complex and difficult, but doable. We need to put our heads together and find new ways of working together putting farmers, food & nutrition and climate at the centre of an extensive consultative process.

In my view, the process to kickstart ‘Amrit kaal for Farmers’ should start with a serious dialogue on Food System Transformation.

(The writer is former Secretary, Food & Agriculture, Govt. of India)

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group