Indian Cities Struggle with Extreme Heat, Short-Term Fixes Dominate Action Plans

A new report by SFC finds that India’s heat actions rely on short-term, reactive measures, underemphasizing long-term solutions—an inadequate approach as heat waves intensify.

A new report by the Sustainable Futures Collaborative (SFC) has raised concerns about India's preparedness for intensifying heat waves. The study, Is India Ready for a Warming World?, examines how nine major Indian cities are preparing for the growing threat of extreme heat. These cities—Bengaluru, Delhi, Faridabad, Gwalior, Kota, Ludhiana, Meerut, Mumbai, and Surat—together make up over 11 percent of India’s urban population and are among the most at-risk cities to future heat.

The report, the first of its kind to assess multiple cities, finds that while all nine cities focus on immediate responses to heat waves, long-term actions remain rare. Where such measures do exist, they are poorly targeted. Without effective long-term strategies, India is likely to see a higher number of heat-related deaths due to more frequent, intense, and prolonged heat waves in the coming years.

Experts warn that India's current approach remains reactive, focusing on immediate relief rather than future-oriented adaptation.

Short-Term Fixes Dominate, Long-Term Measures Lacking

“These findings are a warning about the shape of things to come. With the ongoing retrenchment of global decarbonisation efforts, it will fall upon countries in the Global South to rapidly adapt to a hotter, more dangerous future. While progress on systems to respond to ongoing heat waves is both necessary and urgent, equal attention needs to be paid to gearing up for the future,” said Aditya Valiathan Pillai, Visiting Fellow at SFC and doctoral researcher at King’s College London.

“Many of the long-term risk reduction measures we focus on will take several years to mature. They must be implemented now, with urgency, to have a chance of preventing significant increases in mortality and economic damage in the coming decades. At its core, this calls for the re-imagination of how India’s cities expand and develop,” Pillai added.

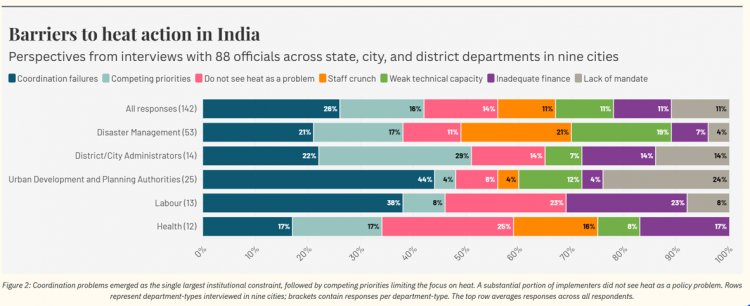

For the analysis, SFC conducted 88 interviews with city, district, and state government officials responsible for implementing heat resilience measures. While all cities reported implementing short-term emergency actions—such as access to drinking water, adjusting work schedules, and increasing hospital capacity—these responses are largely driven by emergency directives from national and state authorities. Heat Action Plans (HAPs), which are meant to provide long-term strategies, appear weakly institutionalized and have had little impact on policy decisions.

“Our findings show that disaster governance at the sub-national level in India is still driven by the logic of providing ex-post facto relief measures. Such an approach will fall short in limiting the impacts of extreme heat as the world warms. This calls for an urgent need to complement these measures with proactive, long-term risk mitigation strategies that will build the resilience of institutions and communities against the risks posed by extreme heat,” said Ishan Kukreti, Programme Lead at SFC.

Institutional Challenges and Funding Gaps

The study highlights major gaps in heat actions, including the absence of household or occupational cooling measures, insurance coverage for lost work, fire management services, and electricity grid retrofits to improve reliability and distribution safety. While some cities have taken steps such as expanding local weather stations, mapping urban heat islands, and training heat plan implementers, these efforts remain inconsistent.

Other long-term actions, such as increasing urban shade, expanding green cover, and deploying rooftop solar panels for active cooling, are not being adequately targeted at the most heat-vulnerable populations. Over two-thirds of respondents reported adequate funding for short-term heat actions. However, long-term climate adaptation efforts lack dedicated financial resources. Institutional challenges—including poor coordination between departments, personnel shortages, and weak technical expertise—further hinder effective heat resilience efforts.

Lucas Vargas Zeppetello, Assistant Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, emphasized the urgency of long-term planning. “With increasing global mean temperatures, it's imperative to prepare for extremely dangerous combinations of temperature and humidity that have no historical precedent to become more common. Pre-emptive, long-term strategies for dealing with heat are central to this effort,” he said.

As extreme heat becomes more severe, researchers stress the need for immediate action to transition from short-term fixes to structural, long-term resilience-building measures before the crisis worsens.

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group