Natural farming needs scientific evaluation, implementation in phased manner

Small-scale initiatives should be undertaken to evaluate the outcomes of natural farming. If encouraging results are observed, the approach can be gradually expanded. It is important to understand that simply creating a mission does not guarantee success.

The central government has been promoting natural farming, zero-budget farming, and organic farming for several years. For the first time, however, this effort is being elevated to mission mode. Recently, the Cabinet approved the National Mission on Natural Farming (NMNF) with a central scheme worth ₹2,481 crores. Out of this, the central government will contribute ₹1,584 crores, while the states will contribute ₹897 crores.

Implementing the scheme in mission mode makes achieving results more practical. The government’s objective behind promoting natural farming is to encourage chemical-free agriculture, which would provide chemical residue-free agricultural products to consumers and improve soil health. This initiative also aims to reduce crop production costs and boost farmers' income.

The mission targets introducing natural farming on 15 lakh hectares of land and involving one crore farmers. With approximately 14 crore farmers in India, bringing one crore of them into natural farming is a significant step. While the plan is ambitious, it is also aimed at improving human health, soil health, environmental sustainability, and climate adaptability in the face of emerging agricultural challenges.

Soil health is deteriorating, and even though the government enforces strict standards for agrochemicals used in crops to ensure that chemical residue remains within permissible limits, reality often differs. The chemical residue levels in fruits and vegetables frequently exceed prescribed limits, and a thorough investigation could reveal startling statistics.

The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) is responsible for ensuring that food products harmful to consumers' health do not reach the market. Recently, representatives of major food exporters admitted in discussions with this author that while grapes exported to Europe and the U.S. meet strict standards, the quality of the same products for the domestic market is significantly lower.

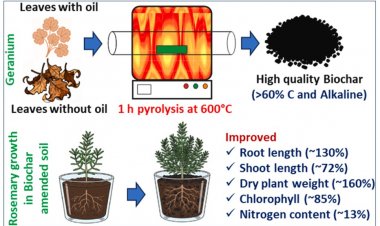

Imbalanced use of fertilizers is also damaging soil health, with organic matter in the soil being nearly depleted in many areas. Declining soil fertility is increasing the use of chemical fertilizers, and record consumption of urea and other fertilizers is being observed.

Against this backdrop, natural farming seems like an attractive option. The mission approved by the government was announced in this year’s budget. In previous years, there was discussion about natural farming, zero-budget farming, and organic farming. The government also announced chemical-free farming along the banks of the Ganga River. However, these efforts have not been very successful. Additionally, regenerative agriculture is being promoted, with scientists supporting the idea as it allows crop residues to remain in the field, reducing repeated plowing costs. However, this option has not advanced beyond experimental stages.

Under the mission for natural farming, agricultural science centers, state agricultural universities, and other institutions will participate. Demonstration farms will be established, 15,000 clusters will be created, and 10,000 bio-input resource centers will be set up. The production of bio-inputs like Bijamrit and Jeevamrit will be encouraged. Certification processes for natural farming will be simplified and expanded, aiming to create a robust ecosystem.

However, it would be better for the government to first conduct a scientific assessment of natural farming. Crop selection is necessary because it may not be practical to include all crops simultaneously. Data on the impact of natural farming on productivity and farmers' income must be gathered, along with clarity on whether this system provides economic benefits to farmers.

Agriculture is an economic activity for farmers, a business, and they will adopt new practices only if they see better economic returns. India’s food self-reliance depends on better agricultural production. For several crops, especially pulses and oilseeds, India still relies heavily on imports. Despite record government estimates for wheat production, prices are rising, and exports are banned. If prices increase further, imports may become necessary. Therefore, any significant experiment must consider ground realities.

The availability of better markets is a crucial aspect of this entire effort. Many farmers in the country have adopted organic farming on a large scale, but they often have to sell their organic products at the same price as conventional ones. They do not receive the premium price that should compensate for reduced yields. However, the government has made a significant move by establishing the National Organic Cooperative Limited, a multi-state cooperative, which could aid the success of the natural farming mission. Certification remains a major issue, and the existing framework by APEDA faces criticism for the questionable quality of certified products.

Thus, small-scale initiatives should be undertaken to evaluate the outcomes of natural farming. If encouraging results are observed, the approach can be gradually expanded. It is important to understand that simply creating a mission does not guarantee success. If it did, missions for oilseeds and pulses established decades ago would have made India self-reliant in these products. The reality is that India still imports 60% of its edible oil requirements and remains heavily dependent on imports for pulses.

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group