Paddy procurement starts in Punjab and Haryana on Oct 3; decision to delay procurement would have virtually negated scientific achievements

When on Oct 2 the farmers in Haryana and Punjab protested the central government’s decision to begin paddy procurement from Oct 11 instead of from Oct 1, the government changed its mind and announced that the procurement would start on Oct 3. The Food Ministry had said that the decision to delay the procurement by 10 days this year had been made because there was a possibility of the retention of excessive moisture in the paddy to be procured on account of prolonged monsoon activity. An interesting point here is that agricultural scientists in the country have developed, as an alternative to paddy varieties that consume more water, short-duration ones that take 20 to 25 days less to mature than the older ones. Most of the area under paddy cultivation has come under these species. But the recent diktat from the Food Ministry officials would have been tantamount to pouring cold water on this achievement.

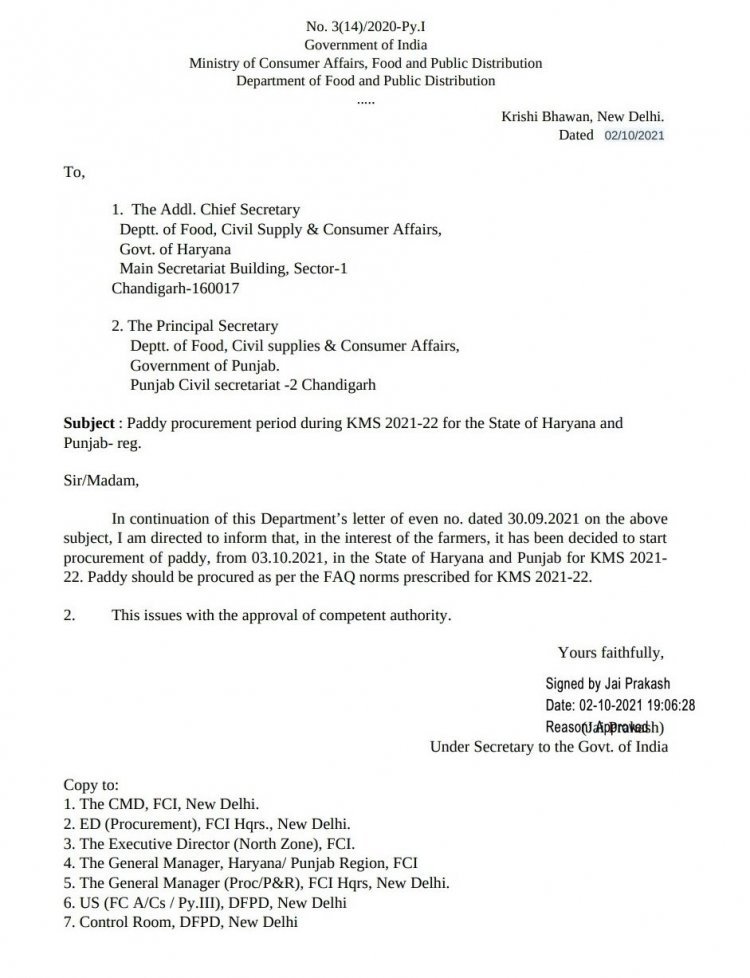

When on Saturday, October 2, the farmers in Haryana and Punjab protested the central government’s decision to begin paddy procurement from October 11 instead of from October 1, the government changed its mind and announced that the procurement would start on Sunday, October 3. The Food Ministry of the central government had said that the decision to delay the procurement by 10 days this year had been made because there was a possibility of the retention of excessive moisture in the paddy to be procured on account of prolonged monsoon activity.

This step of the Food Ministry raises the question as to how a government that claims to always stand by the farmers makes such decisions that compel the farmers to come to the roads. An interesting point here is that agricultural scientists in the country have developed, as an alternative to paddy varieties that consume more water, short-duration ones that take 20 to 25 days less to mature than the older ones. This is why most of the area under cultivation for the crop of paddy has come under these species. But the recent diktat from the Food Ministry officials would have been tantamount to pouring cold water on this achievement.

In fact, the Food Ministry officials bothered only about not procuring paddy with excessive moisture that causes financial loss to the government, but they seem to be unaware of the crop cycle process. Punjab and the Haryana governments have been discouraging the farmers from planting paddy till May-end because it leads to excessive consumption of water. It is due to this that the Pusa-44 variety has been replaced by others that have an equivalent yield but which have a duration (from nursery to crop maturity) shortened by 20 to 25 days. Several of these varieties get ready for harvest by September 15.

The focus of the scientists was on developing short-duration species as the best solution to reduce water consumption by the crop of paddy. And they even delivered. Released in 1993, the Pusa-44 variety, which has an average yield of 32 quintals per acre, dominated the area under paddy cultivation for a long time. But this variety takes 125 days from transplanting to maturity. If you add the 25-30 days of the period in the nursery, the duration comes to 150-155 days. This was why the farmers would start transplanting it as early as mid-May, which is also the time when water consumption in the field is at its highest.

Things changed in 2013, however, when the PR-121 variety of the Punjab Agriculture University (PAU) came to the fields. This variety gets ready in 110 days and its productivity is 30.5 quintals per acre. From 2013 to 2020, nine new paddy varieties were released that had a crop duration of 93 to 117 days. And their yield is in the range of 29.5 to 31.5 quintals per acre. The development of these varieties has brought the area under cultivation for Pusa-44 to almost nil in Punjab. Thus, while this work of the agricultural scientists has reduced the farmers’ costs, it has also been profitable for paddy in Haryana and Punjab on the water consumption front.

The question now arises: how long can you keep a mature crop standing in the field? There comes a time when grains start falling down in the fields. Given this situation, had the procurement been delayed by 10 days, what option would the farmers have been left with? They could either have left the crop standing in the field or stored it after harvest.

The ground reality is that majority of the farmers in Punjab and Haryana use the combine for paddy harvesting. The combine threshes the paddy along with the harvesting and puts it in the trolley. The farmer takes it directly to the mandi and sells it to the government. Now, if the farmers had delayed the harvesting, they would have to suffer crop loss. On the other hand, had the harvesting been done on time, they would have to store the harvest either in the fields or at home and then load it in their trolleys to take it to the mandi. If the work that is ideally finished on the day of harvest itself had been left pending for a week or 10 days, both the work and the costs involved were bound to have gone up.

The story does not end here. If the farmer delays the paddy harvesting, he will be left with less time to prepare the field for wheat. And this leads to a greater probability of an increase in incidents of paddy stubble burning by the farmers. The probability is reduced if the harvesting is done on time because farmers then have 20 to 25 days to prepare the field. Now, if you join the dots, the Food Ministry’s decision to delay paddy procurement is also linked to an increase in pollution in Delhi, because a delayed paddy harvest in Punjab and Haryana implies an increase in incidents of stubble burning there, which consequently leads to threats of pollution in Delhi.

If we consider the entire episode, the Food Ministry’s decision to delay paddy procurement would have been tantamount to pouring cold water, on the one hand, on the efforts of the agricultural scientists to develop short-term crops, and on the other, on those of the Punjab and Haryana governments to adopt short-duration paddy species to save water. Besides, the farmers would have had to suffer economic losses and aggravating troubles due to the entire process. It is only when the officials fail to understand the ground reality that we get to see such decisions.

It is a different matter, however, that the central government had to make the decision to start paddy procurement in Punjab and Haryana from October 3, thanks to the farmers’ massive protests and agitation. In fact, the farmers have been agitating against the three new central farm laws for about a year. And thanks to this, the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM) took the step to go for protests on October 2 under their solidarity, which forced the government to make the decision to go for paddy procurement from October 3.

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group