Local Institutions for Global Challenges

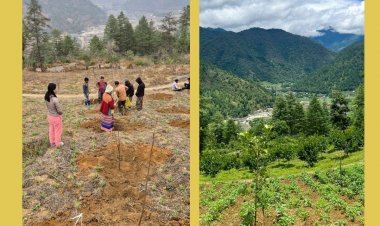

Farming faces several global challenges. Rather, the local challenges that farmers face on the ground have taken global proportions. The climate crisis is one such issue. The other equally urgent is the loss of agricultural biodiversity.

Farming faces several global challenges. Rather, the local challenges that farmers face on the ground have taken global proportions. The climate crisis is one such issue. The other equally urgent is the loss of agricultural biodiversity. Agrobiodiversity is a critical component of sustainable agriculture, ensuring food and nutrition security, environmental health, and resilience against climate change.

The importance of conversation and sustainable use of biological diversity (biodiversity) as a ‘common concern of humankind’ was recognized in international law through the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). CBD was born in 1992 at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also called the ‘Earth Summit’ held at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. India was amongst the 150 countries that signed the CBD then.

The same year the Constitution (73rd Amendment) Act was passed, which established Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs).

Among other things, it provided for PRIs to be institutions for local self-governance. They can exercise powers and perform functions at the village level as the state legislature, by law, provides. The powers, authority and responsibilities of Panchayats (as provided in Article 243G of the Constitution of India) extends to matters listed in the Eleventh Schedule. The very first matter on this list of 29 matters in the said Schedule is ‘Agriculture’. Agriculture sans biodiversity can neither be living and thriving nor be resilient.

The Indian legislature passed the Biological Diversity (BD) Act in 2002 in line with the CBD. Section 41 of the BD Act prescribed a new local-level institution – the Biodiversity Management Committee (BMC). Every local body was required by law to set up a BMC.

In 2004, the Union Government issued the BD Rules, wherein the constitution and the function of such BMCs were laid down in Rule 22. As per the rule, a BMC was to comprise six persons nominated by the local body, of whom not less than one third must be women, and not less than 18 percent should belong to the SC/ST category. A BMC was to be headed by a chairperson elected from among the members of this committee. Two decades later on 22 October 2024, a new set of BD Rules have been issued by the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEF&CC). The rule (Rule 22) on the constitution of BMC has been removed. The BD (Amendment) Act, 2023 lays down:

(1B) The composition of the Biodiversity Management Committee shall be such as may be prescribed by the State Government:

Provided that the number of members of the said Committee shall not be less than seven and not exceeding eleven.

The definition section of the new BD Rules [Rule 2(1)(d)] simply defines a BMC as established under sub-section (1) of section 41 of the Act. Therein, the BD Act states that the functions of the BMC are promoting conservation, sustainable use and documentation of biological diversity including preservation of habitats, conservation of land races, folk varieties, cultivars, domesticated stocks and breeds of animals and microorganisms and chronicling of knowledge relating to biological diversity.

As per the data on the web site of the National Biodiversity Authority, India has a total of 2,77,688 BMCs (2,72,963 BMCs in the 28 states and 4,980 BMCs across the 8 Union Territories). Against this, there are 731 Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs) in the country. These KVKs function under the 11 Agricultural Technology Application Research Institutes (ATARIs) of the ICAR, which come under the Division of Agricultural Extension.

The KVKs have been the via media to bring technology to farmers. The BMCs can be the means of carrying the message and material of biodiversity and its related knowledge to the National Agricultural Research and Education System (NARES) from the farmers. While BMCs have been and continue to be sources of both genetic resources and their know-how from the biodiversity-keepers on the ground to the formal R&D system, their potential to become spaces through which biodiverse agricultural practices, whether on seeds or breeds, needs to fully realised. State governments can breathe new life into these biodiversity institutions.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) was adopted in 2022 at a conference of the CBD. The GBF is a plan to restore biodiversity. Its key elements are 4 goals for 2050 and 23 targets for 2030. It is essentially a post-SDGs 2030 pathway for the world to live in harmony with nature by 2050. The pathway puts biodiversity at the centre. Twenty years after passing the BD Act, India endorsed the GBF. It has also conveyed its commitment to the first phase of the GBF campaign: “The Biodiversity Plan: For Life on Earth”.

The local institutions closest to biodiversity on the farm and the farmer, if kept alive, will not only help meet the goals for sustainable lives and livelihoods but also help address global challenges.

A DEFINITION OF AGROBIODIVERSITY

The variety and variability of animals, plants and micro-organisms that are used directly or indirectly for food and agriculture, including crops, livestock, forestry and fisheries. It comprises the diversity of genetic resources (varieties, breeds) and species used for food, fodder, fibre, fuel and pharmaceuticals. It also includes the diversity of non-harvested species that support production (soil micro-organisms, predators, pollinators), and those in the wider environment that support agro-ecosystems (agricultural, pastoral, forest and aquatic) as well as the diversity of the agro-ecosystems.

Source: FAO, 1999a

TARGET 10 of GBF

Ensure that areas under agriculture, aquaculture, fisheries and forestry are managed sustainably, in particular through the sustainable use of biodiversity, including through a substantial increase of the application of biodiversity friendly practices, such as sustainable intensification, agroecological and other innovative approaches, contributing to the resilience and long-term efficiency and productivity of these

production systems, and to food security, conserving and restoring biodiversity and maintaining nature’s contributions to people, including ecosystem functions and services.

(The author is a legal researcher and policy analyst based in New Delhi. She has been working on a range of issues around sustainable agriculture and biodiversity conservation. Contact: emailsbhutani@gmail.com)

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group