Outrage at Narayana Murthy's 70 hrs-week! Farmer logs in over 98 hrs

What did Murthy say? India’s work productivity is one of the lowest in the world. Our youngsters must say: ‘This is my country; I want to work 70 hours a week'. The outpouring was swift and ruthless! The debate was largely urban and that too in big cities. India of 140 crore people is not restricted to 4-5 metropolitan cities but debates like this must be taken in the larger context as well. And why not include our villages as well?

Infosys founder Narayana Murthy's call to young Indians to work for 70 hours a week has caused quite a stir amongst middle class employees who have poured outrage on this suggestion that made some other industry leaders hopeful for further 'labour reforms' of this kind.

What did Murthy say? India’s work productivity is one of the lowest in the world. Our youngsters must say: ‘This is my country; I want to work 70 hours a week'. The outpouring was swift and ruthless! The debate was largely urban and that too in big cities. India of 140 crore people is not restricted to 4-5 metropolitan cities but debates like this must be taken in the larger context as well. And why not include our villages as well?

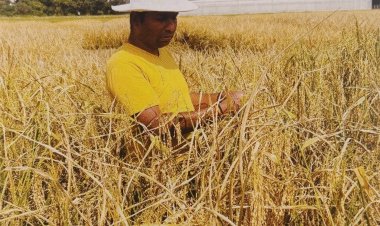

Let's take a typical family of five-six members in a village of western Uttar Pradesh or neighbouring Haryana and see how many hours they work all seven days a week. By the way, there is no such thing called 'Sunday' in the rural economy. The grind continues Sunday through Sunday.

Depending on the season, the head of a family along with his spouse would leave bed no later than 5 in the morning. As per the traditional family division of work, the male head of the family would attend to the family livestock - giving fodder to cows or buffaloes, while his better half would get into the morning chores, chiefly the process of churning of overnight curd and separating butter and butter milk. She would also step in and help her husband in tending the cows or buffaloes.

This would take about two hours after which a small break would be utilised for breakfast comprising Rotis (chapatis) with butter and a glass of Lassi (butter milk) or even a big mug of tea. They get back to work as the village milk man enters the house and the couple starts milking their loved animals. Post this exercise, he would head for the farm (Khet) and she would attend to children, giving them food and sending them to school. Domestic animals have to be again attended to, this time by the lady alone.

This would go on till about 12.30-1 pm, when there would be a decent break of about an hour or so. But the couple has already logged in 7-8 hours. The afternoon and evening routine till night would take a minimum of another six hours. It would safely mean 14 hours a day or 98 hours a week, against 70 hours a week as suggested by Narayana Murthy!

An overwhelming majority of Indians - both in cities and villages - do work hard and should not be blamed for low productivity. A cab driver logs in a minimum of 12 hours a day, so his fellow driver works full time for a company executive. Security guards manning gates in housing societies work 12 hours a day. Small shopkeepers do spend 10-12 hours a day.

But they do not make Murthy's suggestion ideal. His apparent reference was to those in the corporates, who too end up working for at least 8 hours a day or between 40-45 hours a week. These jobs do not involve drudgery of a farmer or a rural labourer, but they require a lot of mental occupation and are not without stress.

The problem of low productivity is not an absence of commitment on the part of us- Indians, but the cumbersome systems and lack of modernisation whether in cities or in villages. Drudgery of animal rearing is the same in our villages today as was the case five decades ago. We need to modernise our practices in our village households, farms, mandis so that they can be integrated into smart and productive supply chains of both consumption and production.

Murthy is a well-meaning iconic first-generation industry leader. His suggestion has to be contextualised in the Indian context and the ground realities.

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group