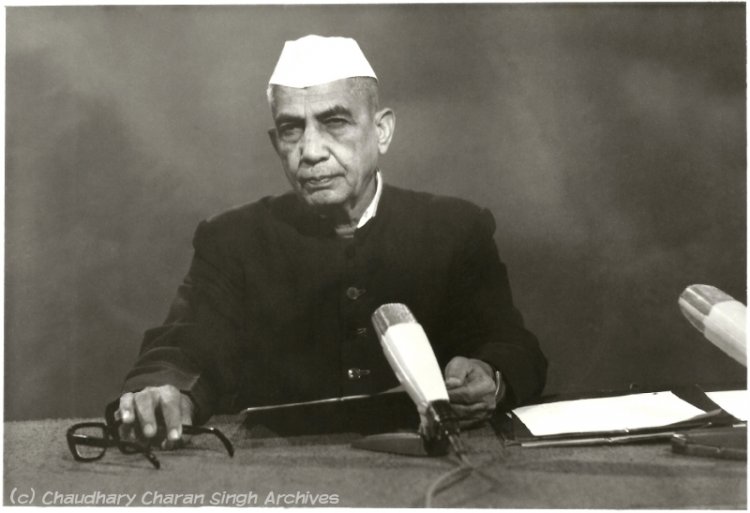

Charan Singh’s greatest contribution: Resistance to collectivization

Mahatma Gandhi and Jayaprakah Narain never ran any government, but they were as important as any viceroy or prime minister in the twentieth century. Therefore, Charan Singh should not be judged just by his place in the power structure but by his achievements. And his biggest achievement was his successful fight against the evil of collectivization of agriculture.

In India, success and often even greatness in politics is measured in terms of the importance of rank and station: which office a politician holds, the duration for which they hold that office, and so on. The metrics are patently wrong; for example, Mahatma Gandhi and Jayaprakah Narain never ran any government, but they were as important as any viceroy or prime minister in the twentieth century. Therefore, Charan Singh, who was recently awarded Bharat Ratna by the Narendra Modi government, should not be judged just by his place in the power structure but by his achievements. And his biggest achievement was his successful fight against the evil of collectivization of agriculture.

Encyclopedia Britannica defines collectivization as the “policy adopted by the Soviet government, pursued most intensively between 1929 and 1933, to transform traditional agriculture in the Soviet Union and to reduce the economic power of the kulaks (prosperous peasants). Under collectivization the peasantry were forced to give up their individual farms and join large collective farms (kolkhozy).”

The consequences were catastrophic: “Output fell, but the government, nevertheless, extracted the large amounts of agricultural products it needed to acquire the capital for industrial investment. This caused a major famine in the countryside (1932-33) and the deaths of millions of peasants,” according to Britannica.

In China, the results were no different. “In 1955 the Maoists speeded up the process of agricultural collectivization,” says Britannica. “After this came the Great Leap Forward, a refinement of the traditional five-year plans, and other efforts at mobilizing the masses into producing small-scale industries (‘backyard steel furnaces’) throughout China. The experiment’s waste, confusion, and inefficient management combined with natural calamities to produce a prolonged famine (1959-61) that killed 15 to 30 million people.”

The horrors of socialism and communism—over 100 million people dead all over the world because of collectivization, purges, mass murders that communist tyrants carried out regularly—came to the fore mostly after the end of the cold war. In the 1950s, the then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru was fascinated with the utopian promises made by Karl Marx and his followers. This was the reason that Nehru was promoting joint and cooperative farming.

But Charan Singh, who had an agrarian background, knew better. What was more important was that he had the courage to slam Nehru’s ideas, for there were other leaders too with their roots in villages but they didn’t oppose the dangerous idea of collectivization. This was akin to a Bharatiya Janata Party leader opposing Prime Minister Narendra Modi on a policy issue, for Singh was a member of the grand old party at that time. He made his views known to all at the Congress’s annual session in Nagpur in 1959.

In the same year he wrote Joint Farming X-rayed: The Problem and Its Solution, which present cogent arguments against Nehru’s quixotic ideas. “Attachment to the land is a universal trait in the peasantry of all countries. The French peasant, for instance, calls his land his ‘mistress’,” Singh wrote.

He went on to write, “Human nature is the same everywhere. Here, our peasant calls his land Dharti Mata—Mother Earth—inasmuch as it provides sustenance for all living things. Everywhere the peasant is a firm believer in property striving for independence. Hence a collectivist economy will meet with his emotional resistance from the start. Ultimately it is not a question of economic efficiency or of form of organization, but whether individualism or collectivism should prevail. Peasantry represents not only a certain form of economy but also a certain way of life. Within the peasantry those characters, traits and moral forces are most pronounced which resist the tendency towards collectivism and of being leveled down into a uniform mass.”

It is unfortunate that Charan Singh is seen as a leader of farmers who managed to become prime minister for a few weeks. The reason is that people in our country don’t know much about, in the first place, the calamities that were brought in the countries where collectivization was introduced and, secondly, the role he played in forestalling the impending catastrophe.

Charan Singh was also aware of the pernicious effect socialist practices like collectivization have on democracy. He wrote, “The plant of freedom cannot thrive on the soil of collectivized farm which is a large joint undertaking, nor was it intended to thrive by its founders. When we find in India, therefore, persons who profess belief in democracy yet advocate establishment of huge, jointly-operated units of production as the remedy of our rural problems, one can only sympathize with them and wish they knew the countryside and the object of their arm-chair solicitude before offering solutions.”

Thankfully, Charan Singh knew the countryside.

(The author is a freelance journalist)

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group