The Challenges before India’s Emergence as an Agricultural Export Hub

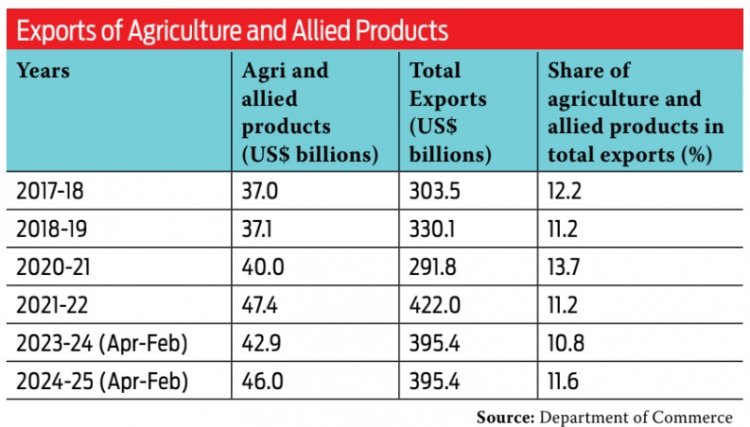

Increase in exports of agricultural commodities since 2018 was not only far less than the target of “doubling by 2022” set in the Agricultural Export Policy, but it was also less than India’s overall exports, which grew by 30%. As a share of India’s total exports, agricultural products’ exports remained between 11-12%, except for 2020-21, the year in which exports of all other products other than food products had suffered sharp decline.

In December 2018, the government announced an ambitious Agriculture Export Policy, the first time it had done so. The significance of an agricultural export policy lay in the fact that it marked a departure from the earlier emphasis of India’s agriculture, namely, to ensure domestic food security. This shift in the focus of agricultural policy was in the offing for quite a while since the ‘Green Revolution’ strategy had long ensured that India was a food self-sufficient country and that there was no possibility of sliding back to import dependence.

The Agriculture Export Policy had several overarching objectives. First, it was framed with a focus on agriculture export oriented production that was to be synchronised within policies and programmes adopted by the Government of India. Secondly, the policy emphasised the need to have a “farmer centric approach” focused on improved income generation through greater value addition, which would help to minimise losses across the value chain. Thirdly, the policy underlined the need for a farmer oriented strategy that could achieve the twin objectives of food security and a prominent agriculture exporter of the world.And finally, the intention of policy was to provide a boost to the food processing industry, which would increase India’s share of value added processed products in its agriculture export basket enabling it to emerge as a major player at the global level.

Besides its overarching objectives, the Agriculture Export Policy had a number of specific targets, which was an interesting feature of this policy. One, to double India’s agriculture exports to $60 billion by 2022 by doubling India’s share in world agricultural exports through integrating with the global value chain at the earliest, and to enable farmers to get benefit of export opportunities in overseas markets. In fact, promotion of agricultural exports was seen as sine qua non for meeting the objective that the government had set in 2016 for doubling the farmer’s income by 2022.Two, diversifying the export basket, destinations and boost high value and value added agricultural exports including focus on perishables. Three, to provide an institutional mechanism for pursuing market access, tackling barriers and to deal with sanitary and phytosanitary issues, or human, animal and plant life and health standards that are critical to expanding India’s footprint in the global markets.

The contentious farm reforms introduced in 2020 was yet another move for transforming India into an agricultural export hub. The Essential Commodities Act. 2020, deregulated the markets for agricultural commodities and was expected to provide a fillip to exports.The Act was amended to deregulate the market and to, therefore, give freedom to produce, hold, move, distribute and supply to harness economies of scale and attract private sector as well as foreign direct investment into agriculture sector. The government argued that India has become surplus in most agricultural commodities, but farmers have been unable to get better prices due to lack of investment in cold storage, warehouses, processing, and export as “the entrepreneurial spirit”was dampened due to restrictions on stock holding imposed by the Essential Commodities Act.

In 2022, the Directorate General of Foreign Trade adopted the Districts as Export Hubs (DEH) initiative to identify agricultural and other products having export potential in 733 districts. This initiative has three specific objectives in regard to promoting exports: (i) to diversify India’s export destinations and to boost high-value and value-added agricultural exports including focusing on perishables, (ii) to promote exports of novel, indigenous, organic, ethnic, traditional, and non-traditional agricultural products and (iii) to enable farmers to benefit from export opportunities. The Foreign Trade Policy of 2023 provided legitimacy to the DEH initiative through establishment of institutional mechanisms that would enable identified districts of the country to become export hubs. The District Export Promotion Committees were tasked with the responsibility of identifying products and services with export potential in 765 districts (in 2025), addressing bottlenecks for exporting these products/services, supporting local exporters/manufacturers to scale and find potential buyers outsideIndia aimed at promoting exports.

With considerable efforts being put on promoting agricultural exports since 2018, it would be useful to assess the performance since the Agriculture Export Policy was adopted. It may be recalled that when it was unveiled, one of the overarching objectives of this policy was to double exports of agricultural products by 2022.

The challenges that the country faces in establishing itself as a major agriculture export hub can clearly be seen from the developments since the agricultural export policy was adopted in 2018. Available data from the Directorate General of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics of the Department of Commerce shows that exports of agriculture and allied products increased from about $37 billion in 2018-19, to about $46 billion in 2024-25 (April to February), or about 24%. Increase in exports of agricultural commodities since 2018 was not only far less than the target of “doubling by 2022” set in the Agricultural Export Policy, but it was also less than India’s overall exports, which grew by 30%. As a share of India’s total exports, agricultural products’ exports remained between 11-12%, except for 2020-21, the year in which exports of all other products other than food products had suffered sharp decline.

Increase in exports of non-basmati rice has been remarkable since the turn of the previous decade, when the value of non-basmati rice was just $50 million, but a decade and a half later, exports had increased over 10-fold to $6 billion. In 2020-21, exports of this variety of rice exceeded those of basmati, the most popular agricultural export, for the first time. Increased exports of this variety of rice not only strengthened India’s control over the global rice export market, but also improved the country’s trade relations with several Sub-Saharan African countries, which accounted for a substantial share of this variety of rice exports. In 2024-25, over 51% of the total exports went to this region accounted, Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, and Senegal were the three most prominent markets in 2024-25. Importantly, steep increase in exports of non-basmati rice during the covid-pandemic helped most of the importing countries overcome the strains they had experienced in the aftermath of the covid-pandemic.

Six largest commodity groups in terms of exports in 2024-25, namely rice, marine products, spices, buffalo meat, sugar, and oilmeal accounted for about 63% of total exports of agriculture and allied products. The share of these products in the total exports of agriculture and allied products was higher at about two-thirds in 2018, and after peaking in 2020-21, this figure had declined. Rice exports grew the fastest (48%) during this period, on the back of an almost doubling of non-basmati rice exports, despite the fact that the government had imposed a ban on rice exports between July 2023 and September 2024 to stabilise the domestic market.

However, the government allowed exports to countries to meet their food security needs and based on the request of their Government. On the other hand, exports of marine products declined between 2017-18 and 2024-25, while buffalo meat exports rose marginally by 3%. Sugar exports increased by 37%, despite suffering from the production cycles, and oil meal exports declined by nearly 19% since 2017-18.

Bullish expectations on agriculture exports had built-up since the end of the previous decade, but this had all but disappeared all too quickly. The expectations suffered a sharp reversal of in 2022-23, as wheat stocks showed signs of depletion. A major slide-back in wheat production resulted in its exports falling to $54 million in 2023-24, the lowest level since 2011-12. Heat stress adversely affected wheat production from 2023, resulting in a sharp drop in exports to mere $1.6 million during 2024-25. Thus within 3 years, wheat exports had declined from a high of $2.2 billion to $1.5 million, which was a reminder that fluctuations in the production of the major commodity could pose significant uncertainties. Most crops, with the solitary exception of rice, were unable to overcome the typical production cycles over the past few years that posed severe supply constraints. This meant that except for exports of basmati rice, a commodity, India could not establish itself as a major exporter of agricultural commodities.With the sector mired in structural crises, and farmers agitating over the fact that agriculture had ceased to be a profitable business, maintaining the levels production of most crops was clearly a tall ask.

One positive development is the steady increase in the exports of processed agricultural products, including fruits and vegetables. Between 2017-18 and 2024-25, exports of processed products had nearly doubled. India needs to focus more on these products to improve value addition and employment opportunities in the country, and, more importantly, the food processing sector is in a better position to realise the objectives of the Agricultural Export Policy.

Food Safety Standards

Uncertainties in the levels of production were not the only factor adversely affecting India’s exports of agricultural products. A more important factor is the ability to conform to the sanitary and phytosanitary standards that are consistently become more stringent, not only in the advanced countries but also in most advanced developing countries.

The European Union (EU) member states and the United States have comprehensive mechanisms of issuing alerts regarding actual or potential risk arising from import of food products. The EU members have in place a “Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed” (RASFF) for facilitating rapid exchange of information on levels of risks detected in food or feed. RASFF plays a key role for protecting public health through quick responses regarding food safety issues, including concerns arising from imports.In the US, the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) has the authority to ensure that products imported into the US comply with the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) and other related acts.Imports failing to comply with the FD&C Act are included in “import refusals”, FDA’sfinal decision that a detained shipment is in violation of its laws and regulations.

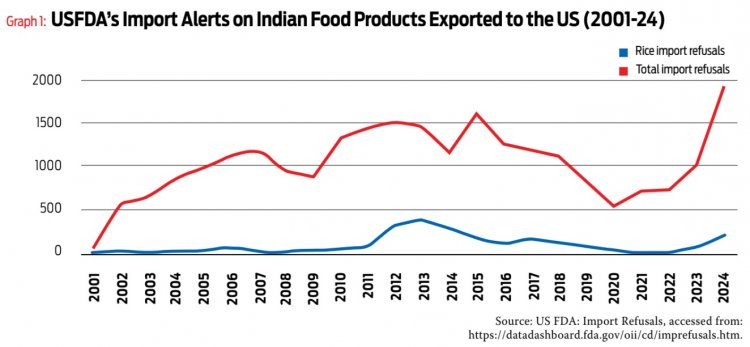

Analysis of the data obtained from EU’s RASFF from 2020 and FDA’s import alerts since 2001 gives an indication on the extent to which Indian exporters of food products are complying with the sanitary and phytosanitary standards that these two jurisdictions have in place. The FDA’s import alerts are available from 2001, enabling a longer term view on how India’s exports of food products have met the test of American standards (Graph 1).

The steep increase in import refusals faced by Indian exports of food to the US since covid-pandemic is surely an area of concern. Even in 2025, the import refusals’ trend has remained unchanged with 766 cases of import refusals being recorded until the end of April. However, import refusals in case of Indian rice imports into the US shows a positive trend overall, though the slightly upward trend since 2021 must not be allowed to increase any further.

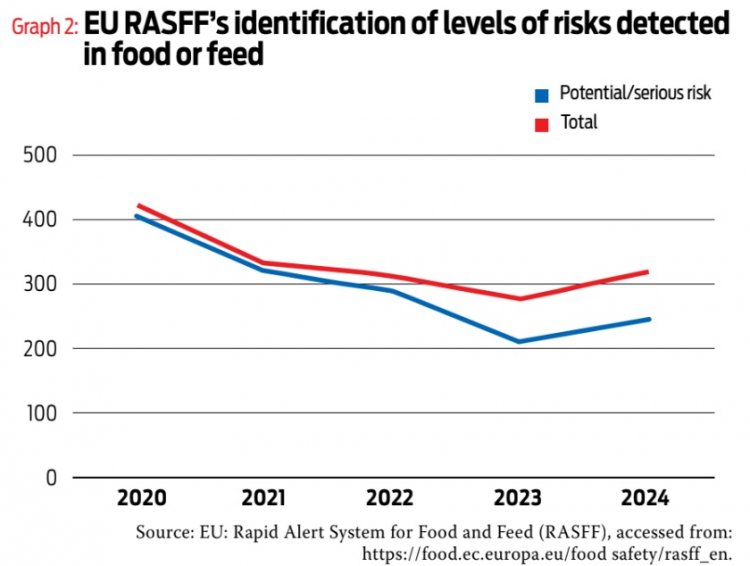

EU’s RASFF flagged 1661 consignments from India containing food or feed as having different levels of risk during 2020 and 2024. However, 12% of these were marked as having “no risk”. The trend of those posing potential/serious risk is captured in Graph 2.Graph 2 which captures the trend of import consignments of food and feed having high levels of risk since 2020 shows an encouraging trend overall, though the moderate increase in 2024 should be taken note of.

The trend during the first 4 months of the current year looks encouraging as 72 cases were identified, of which 12 were not serious. However, the trends of complying to sanitary and phytosanitary standards in the US and the EU show that the government need to pay considerable attention towards developing new institutions and strengthening the existing ones, through which producers and exporters of agricultural products can prepare themselves for overcoming the exacting standards prevailing in global markets. Without this preparedness, India’s ambition of becoming an agricultural export hub would remain largely unrealised.

At the same time, the government must step up its investment in the agricultural sector to provide a sustained boost to production of major commodities which is critical for the country to emerge as a reliable agricultural export hub.

(The writer is Professor, Jawaharlal Nehru University (Retd), Distinguished Professor, Council for Social Development)

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group

Join the RuralVoice whatsapp group